What's Wrong With A Commercial Graphic Novel?

Based on the conversations I've had with aspiring comics creators, there's the common underlying fear when it comes to creative control. They say that they're not sure that a publishing company will honor their creative integrity, and suggest that "a publisher just wants to make money" as something inherently evil. This is the reason why they choose to produce their books independently, using their own money, with a small print run and limited distribution. To them, it's okay that they don't sell a lot, as long as they get their work out.

My question, then, is: why spend all that time and money to get a book out in the first place if you're okay with mediocre sales?

Independent comics creators should worry about the bottom line as much as publishers do. Why? Because a good bottom line ensures the creator of a future in the field. If my graphic novel sold well, I would make enough to produce another book, and another. If I made a graphic novel and it hardly made a sales dent, then what's going to stop me from shifting gears towards another career altogether? What's going to stop me from throwing in the towel?

That's why publishers want to make sure a book sells. They want to keep at the business over the long run. As much as they would want to honor your creative integrity, they also wish that you'd honor their desire to make a decent buck.

This brings up the issue of the "commercial" work, which many seem to translate as "dumb." As we've seen in other media, this isn't entirely the case. In the fiction world, there are literary gems (like those of Murakami and Garcia Marquez) and throwaway fare (fill-in-the-blanks romance novellas), but there are also the commercial and readable works (by Sparks, Patterson, Grisham, etc.) . Same goes for film and television. Each medium has a spectrum that covers general demographic and psychographic preferences.

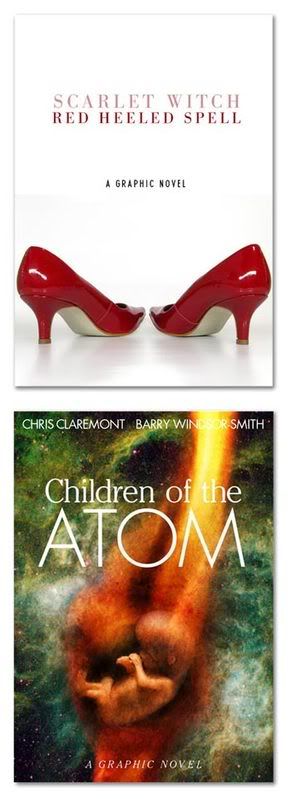

Question is: can the same be said for comics and graphic novels? Think about it. On one end, you have the highly specialized superhero niche, dominated by Marvel and DC. Note that superhero comics isn't commercial mainstream, because while it caters to a certain age group, it focuses specifically on those who like superheroes.

On the other end, you have the comics-as-literature types like Maus, Persepolis, Ghost World, American Splendor, and others. These are the "art house" denizens of the comics world.

So where are the "middle ground" comics? Where are the comics equivalent of CSI, West Wing, Devil Wears Prada, Desperate Housewives, The Bourne Identity, Meet The Fockers, The Sixth Sense, A Thousand Splendid Suns, The Twilight Saga, Gossip Girl, etc.? The kind of comics that have a strong commercial potential (read: are meant to sell) and yet doesn't insult the intelligence of an audience? If there are such comics, why aren't there a lot of them?

As an exercise, think about those commercial movies, novels, and television shows that you love. Now isolate those based mostly on the story--tough, but it can be done. Then ask yourself, are there any comics out there that have similar stories? If there aren't, it might be a good idea to develop one, with the bonus of your adding your unique spin to it. The key here is to develop story ideas that can cater to a commercial audience, but at the same time, allow you to practice your creative integrity.